Liternatura. Some say it’s just a passing trend, that it’s not a real word or, at best, a mere adaptation of the expression ‘nature writing’. What is true, however, is that the English language has always had a soft spot for literature featuring forests, rivers, animals, and nature in general; and that the volume of books attending to that space, to that idea, gave rise to a unique genre, self-named by those who cultivated it: nature writing. In English.

The fact that the Iberian Peninsula has been using the genre’s English name for decades denotes how far removed local authors have been from demonstrating even a minimal interest in filling their pages with their own breath-taking natural spaces and the more or less wild animals that roam around them. As if nature was somebody else’s specialism, as if the English word ‘flower’ were more valid than the Catalan ‘flor’. For decades, books on travel and nature have been regarded as a literary by-product, as if both genres did not, in their own right, represent the most tremendous expression of biodiversity. Why?

In the wake of the late Franco regime, the Spanish Transition held up the city as the centre of freedom and money, displacing the villages, the countryside and the suburbs to stale, sad and unprofitable corners. The city-dwellers bought the story, and oddly enough, so did the rural communities. And the literature? Well, that too. For forty years, the literary ecosystem has shared, as a general rule, the socio-political and economic inclinations of a country surrendered to institutions, companies and a media who came to a mutual agreement that everything was fine, that science would right all wrongs, and that hippies, peasants and poets were relics of a bygone era. Few writers have dabbled in the margins beyond the official margins, the ones that have always been a part of our (urban) lives and which do an excellent job of accommodating the well-integrated noir genre. It's as if we forgot that the source of all life on Earth, can be found on the margins of the human margin: in nature.

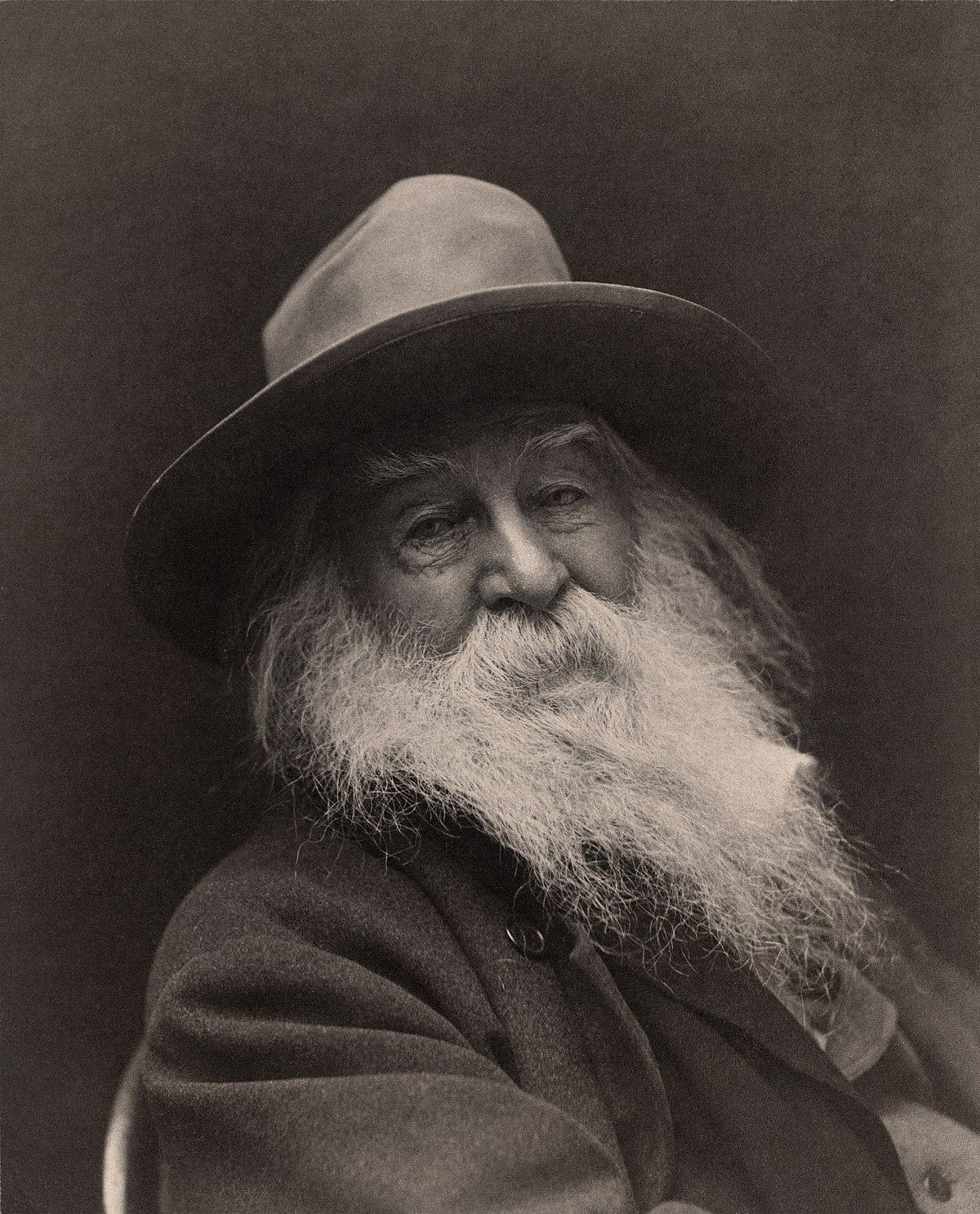

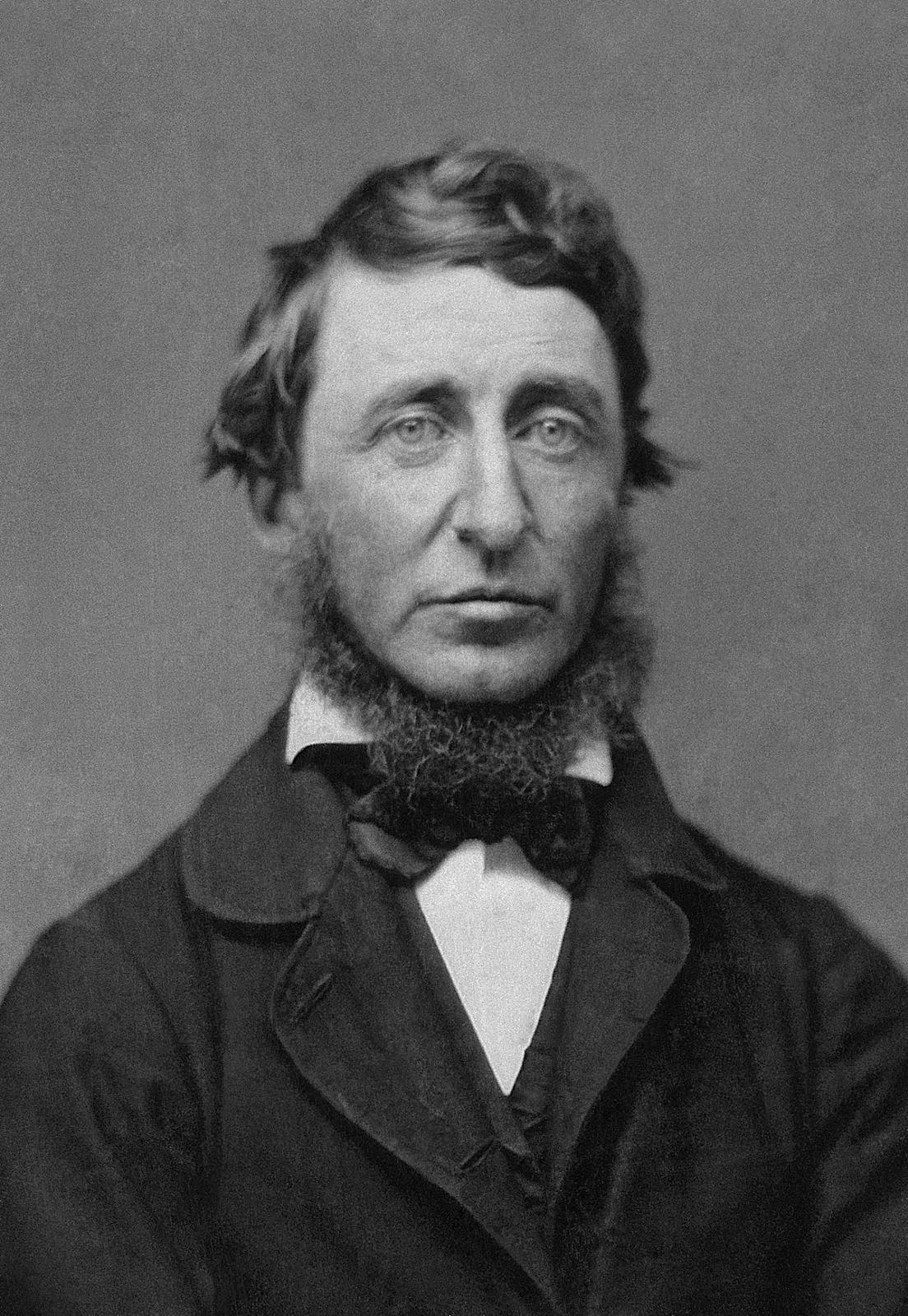

The concept of nature writing is associated, above all, with two colossi born within two years of each other: Walt Whitman and Henry David Thoreau. Realising the implications of the industrial revolution and its iconic railroads, Whitman and Thoreau wrote about orchards, disobedience, and poetry in texts that inaugurated a tradition in their language. From Aldo Leopold and John Muir to Rachel Carson, Wordsworth, Wendell Berry, Robert Macfarlane, Annie Dillard, Paul Kingsnorth, Roger Deakin, Penelope Lively, etc. Over the last five years, Spain and Catalonia have been getting (re)acquainted with the many names on this enviable list, which is why books that impacted on other countries thirty years ago or more are now being published here.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, however, things were quite different. The overwhelming political tensions and distrust in the way much of humanity was making use of machines prompted an ethic linked to an indigenous, pro-nature line of thought. In Catalonia, the movement was spearheaded by the likes of Narcís Oller, Víctor Català, Gaudí, Prudenci and Aurora Bertrana, and gave rise to entities like the Associació Excursionista de Catalunya (the Catalan Hikers Association), which encouraged people to get to know the land, to love it for what it was, for its raw material, and not just as propaganda or abstraction. The Association extended its influence to culture, founding the Institut d'Estudis Catalans (the Institute of Catalan Studies), for example. But the Civil War scorched that seed before it could germinate. Francoism forgot about it entirely. And the Transition gladly inherited the anti-rural developmental blindness of the dictatorship, occasionally counteracted by authors such as Maria Àngels Anglada, Mercè Ibarz, Pep Coll, and of course Josep Pla.

Be that as it may, younger writers who are now discovering the immense quality of these books and authors dedicated, predominantly, to nature writing as they simultaneously suffer the consequences of the environmental chaos of recent times, are now venturing out to openly explore the possibilities of our local nature; its narratives as well. The results are far from equal, we are relearning to familiarise ourselves with the wilder side of our vocabulary. To call a deer by its local name and the flower a flor. To publish unheard-of writers who talk of mycelium and hawks. But these sometimes unaccomplished pages are revealing an intention, the need to occupy a space we have come to view as increasingly necessary, and also, ours.

It’s also true that while Robert Macfarlane and Mark Cocker discuss whether nature writing should send seductively positive messages or radically denounce those who lay waste to our ecosystems; and while Abi Andrews, in her thirties, brilliantly criticises the ultra-masculine gaze which has, until recently, distinguished such writings, we’re still trying to weigh-up whether such literature deserves a native name. But here we are at last. Stammering ‘liternatura’.

In the human realm, identifying with a name suggests a beginning. Maybe the mere act of saying nature writing or liternatura suggests we’re ready to engage in ‘the great conversation’ with nature, as Thomas Berry encouraged. And when we pronounce that name, for example, in Catalonia, we are paying our respects to the Ebro Delta, the Pyrenees, the newt, the broom and the capercaillie; the volcanoes of La Garrotxa and the wetlands of Empordà, to name but a few. We are expressing our will to build something with them.

They say one of the reasons we’re late to take up words like liternatura is because of a lack of dialogue between those who, while loving nature equally, approached it entirely differently. Entrenched in their own perspectives, they drifted further and further apart until they arrived at opposite ends of the spectrum, and for some reason, began to see each other as enemies. Eventually, they burned any bridges between them, established clearly opposing standpoints, and became caricatures of themselves. ‘Individualism is going around these days in uniform’, wrote Wendell Berry. Thus, to this day, some believe that to defend nature you must choose between being a hunter or a far-left ecologist.

So, how have we arrived at this nonsensical position? A few weeks ago, the ecofeminist philosopher Yayo Herrero commented that her European colleagues view Spanish environmentalism as the most radical on the continent. One possible reason is that activists in Spain have had to face, more than any others, a barrage of systematic abuse and disparagement from the powers that be – restaurateurs, estate agents, the media and, of course, politicians – which have been designed to wipe nature from our collective imagination. And so, to counter this trampling and denial, the environmentalists have chosen to shout louder and even more spectacularly. Perhaps.

In any case, the evidence points towards the fact that we’re beginning to realise something has to change. But if we are to achieve that change, we must first change the narrative; the words we use. That change involves presenting nature in all its facets and ambiguities as if it were a character, not only bucolic and fearsome but organically diverse. The more of nature’s many faces we come to know, the more authentic she will seem, and, therefore, the more attractive, seductive, mysterious, complete. The word liternatura may have a key role to play in helping us make that change.