Perhaps it is no coincidence that Josep Maria Benet i Jornet wrote Una vella, coneguda olor (An Old, Familiar Smell), his first theatrical text, a year after the death of Josep Maria de Sagarra, in 1962. He was 22 at the time and the standard bearer of Catalan theatre from the first half of the twentieth century and writer of over 50 plays had died at the age of 67. Just when this popular playwright’s flame was going out, the man who would become the most influential writer in the last 40 years of Catalan theatre was sparking into action. Benet i Jornet decided to write plays when Catalan was not taught in schools, when theatre had been shut away in poets’ houses (Brossa, Espriu, Palau i Fabre, etc.), when everyone took Catalonia’s great theatre tradition for dead.

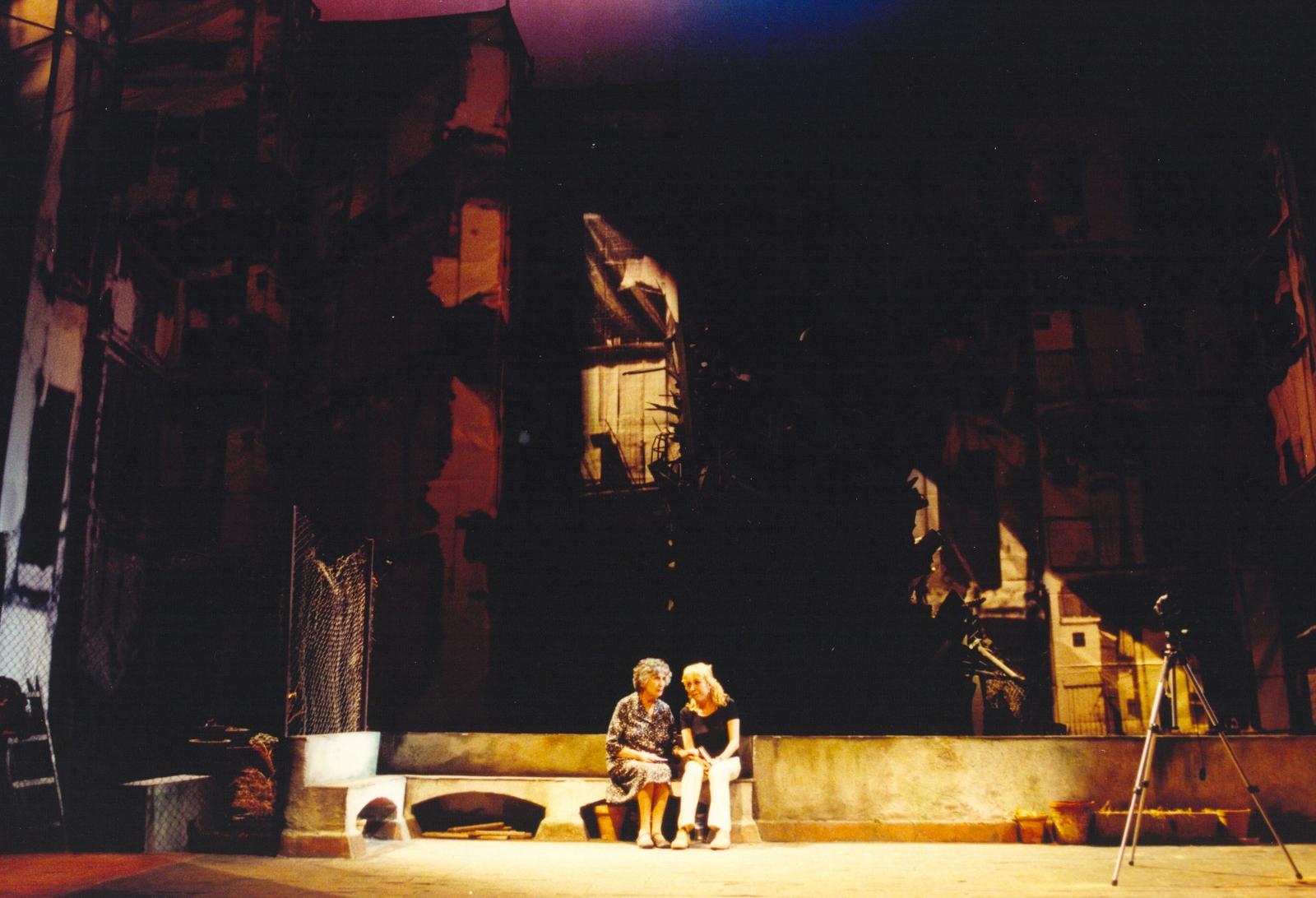

Una vella, coneguda olor is a piece that was intended to be popular, that talks about ordinary people, and that bears similarities to Sagarra’s work in many ways, especially El cafè de la Marina (The Seaside Café) and La rambla de les floristes (The Florists’ Rambla). And it connects the audience with one of Benet i Jornet’s favourite themes: memory. He was obsessed by this theme. In many ways, it is something to do with one of the great writers of the twentieth century, the Neapolitan Eduardo de Filippo, for whom theatre is the most vivid expression of the people and the playwright’s only task is to provide a mirror for the people to see their reflection, to think and to enjoy. For this reason, both the Neapolitan and the Catalan wrote plays about theatre. L’arte della commedia (The Art of Comedy) or Sik-Sik, by one. La desaparició de Wendy (The Disappearance of Wendy, 1974) or E.R. (1994), by the other.

But De Filippo and Benet i Jornet lived in different times. And different circles. The Catalan’s career was on the up in the 1970s, and at that time, in Barcelona, there were very few writers around. He was alone. And in an environment where no one wanted playwrights, as though what Catalan theatre had produced since Pitarra were enough, as though the theatre avant-garde of the time could do without the contemporary text. There was not much more available than Joan Brossa: writer of plays for smaller audiences that were anything but naturalistic. In the rest of the world, it was the glory days of Harold Pinter, Arnold Wesker and Heiner Müller, with the long shadow of Samuel Beckett looming over them. In other words, there was post-dramatic, social, absurd and existentialist theatre. Benet i Jornet, son of a country that wanted to leave behind the long night of Francoism and make a name for itself, wrote Berenàveu a les fosques (You Were Taking Tea in the Dark, 1970), Revolta de bruixes (Witches’ Revolt, 1976) and La desaparició de Wendy), three plays that once again looked at the themes of memory, tradition and legacy, without forgetting about the present. He was still experimenting and did so through classic-style texts, influenced by what had been written in Catalonia in the previous hundred years.

The ’80s was the decade in which Benet i Jornet took on his greatest battle. There were no contemporary playwrights on the stage, and he became a sort of one-person lobby. He saw that it was time for him to make his move, that Sagarra, Guimerà and Rusiñol were great and all, but Barcelona was not Naples, where De Filippo had died a hero, and so he needed to make a new

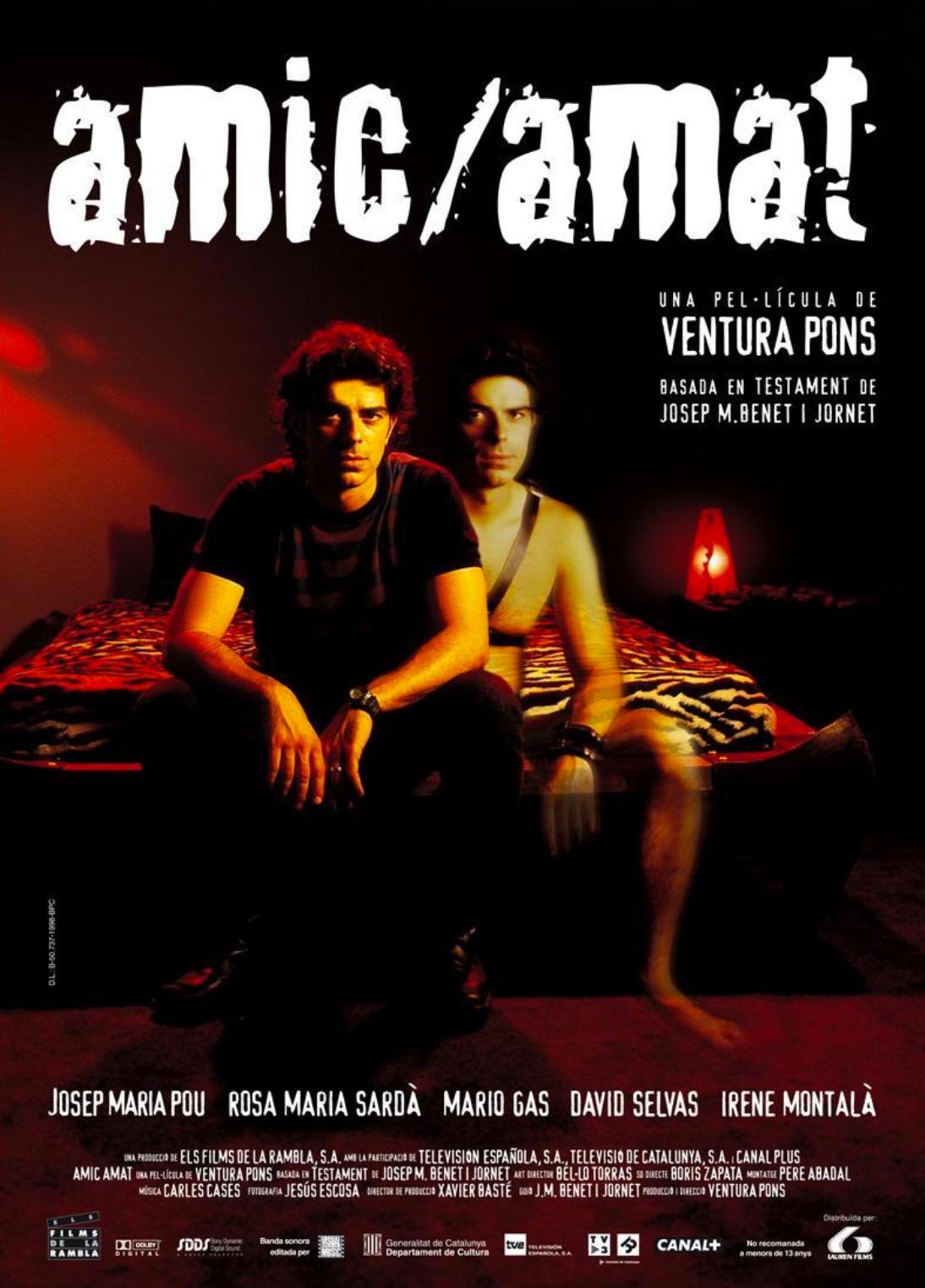

keystone for his theatrical writing. Around this time, he rediscovered David Mamet and went back to Pinter. Thus was born the playwright’s brilliant trilogy, made up of Desig (Desire, 1991), Fugaç (Fleeting, 1994) and Testament (1997). They once again displayed an obsession with memory, broadened into unhappiness and death, but the writing in all three pieces is a lesson in theatrical goldsmithing. Desig, in particular, is a great play ‘without a plot’, according to the writer, and a Pinter-esque piece, bearing resemblances to No Man's Land, for example. It talks about isolation, alignment, through four characters who clash, who never say what they think or why they do what they do. Each of their monologues, which open the scenes, demonstrate Benet i Jornet’s great lyrical capacity and ability to scrutinise his characters’ interior world with language.

Desig was a formal and textual turning point, rounded off by the presence around the playwright of a flock of young writers who wanted to follow in his footsteps. Indeed, the play was directed at the Teatre Romea by Sergi Belbel, who was just starting out at the time. After over twenty years talking to a brick wall, a new generation of playwrights was emerging, and Benet i Jornet took on the task of feeding them, looking after them, guiding them. What’s more, José Sanchis Sinisterra, renowned writer of ¡Ay, Carmela!, had opened the Sala Beckett theatre: finally, contemporary playwrights had a home in Barcelona.

Benet i Jornet also used television as a means of making the most of his popular facet, of attracting bigger audiences. He created the series Poblenou (1993–94), Nissaga de poder (Dynasty of Power, 1996–98) and Laberint d’ombres (Labyrinth of Shadows, 1998–2000), among others, which became a phenomenon in 1990s’ Catalonia. To some extent, they set him free, as perhaps for the first time, he could write the plays he wanted to write, rather than those that society needed. Pinter and David Mamet (writer of The Woods and Oleanna) came knocking at his door, as well as the British writers of his time. It is difficult not to pair Soterrani (Underground, 2008) or L’habitació del nen (The Child’s Room, 2002) with Blackbird by David Harrower or Pinter’s ‘comedy of menace’, including The Birthday Party and The Caretaker, or even with Mamet’s Sexual Perversity in Chicago.

Soterrani is another of Benet i Jornet’s great plays. It could almost have been written by Martin McDonagh. On the stage are two men: one middle-aged, the other older. The younger one is distraught because he doesn’t know how his wife died. The other looks like a nice chap, like a man who has lived his life and never done harm to anyone. The two get tangled up in a lofty dialectical struggle with an explosive ending. Like in L’habitació del nen, in which the protagonists are husband and wife. Two dark plays that embark on an intimate exploration of the path the writer laid in Desig, investigating individual and social unhappiness and bitterness: a road that Catalan theatre influenced by Benet i Jornet has extended with excellent texts like Après moi, le déluge (After Me, the Flood) by Lluïsa Cunillé, Fum (Smoke) by Josep Maria Miró and Justícia (Justice), by Guillem Clua.

Like all great playwrights, he knows that language itself is action. That there can be a great, original, involved plot that grabs the audience’s attention, but the playwright’s main struggle consists of controlling the words their characters utter. Xavier Albertí, the current director of the National Theatre of Catalonia, once told me the following when I was trying to catch him by asking him about Sarah Kane and Benet i Jornet, two supposedly opposite poles: ‘Sarah Kane’s theatre opened up numerous borders in terms of writing techniques, which were extremely important. She taught us that the pain of living can be turned into theatre with a very complex formal conscience. Benet i Jornet does the same with his tools: his is not frivolous theatre, and when he has sought comedy, he has done so from a perspective of social commitment’.

It is when Benet i Jornet flees naturalism in the strictest sense, when he shuts his characters in a room, that the great writer truly appears, the great European playwright. Nearly all of them always look for something that explains who they are, why they do what they do. One of the characters in Salamandra (Salamander, 2005), the Master, says: ‘The world I come from, the music of the names of the things in the world I come from, will disappear. Their world... I don’t know what world it is, but they must have one, and whatever it’s like, it mustn’t disappear. That mustn’t happen. Their world mustn’t disappear. One day, if you want to, talk to our son about the place I came from. So that he knows that other universes existed and so that he defends his own’.

He knew that a butterfly flapping its wings can cause a hurricane, that we are nothing without memory. That everything changes and we have to learn lessons from the past, both in the theatre and in life. Through his theatre and his ability to adapt to new times, Benet i Jornet linked the pre–Civil War theatre tradition with that of the arrival of democracy. He paved the way for generations of writers to arrive on the scene in normal conditions by remaining loyal to his language, to his culture, and by mobilising an audience that wanted to see work by local playwrights. When he was famous thanks to television, he could have made do with continuing to tell stories of tormented families. Instead, he decided to research and write Dues dones que ballen (Two Dancing Women, 2010) and Soterrani to continue to discover who we are.

ANDREU GOMILA

@andgomila