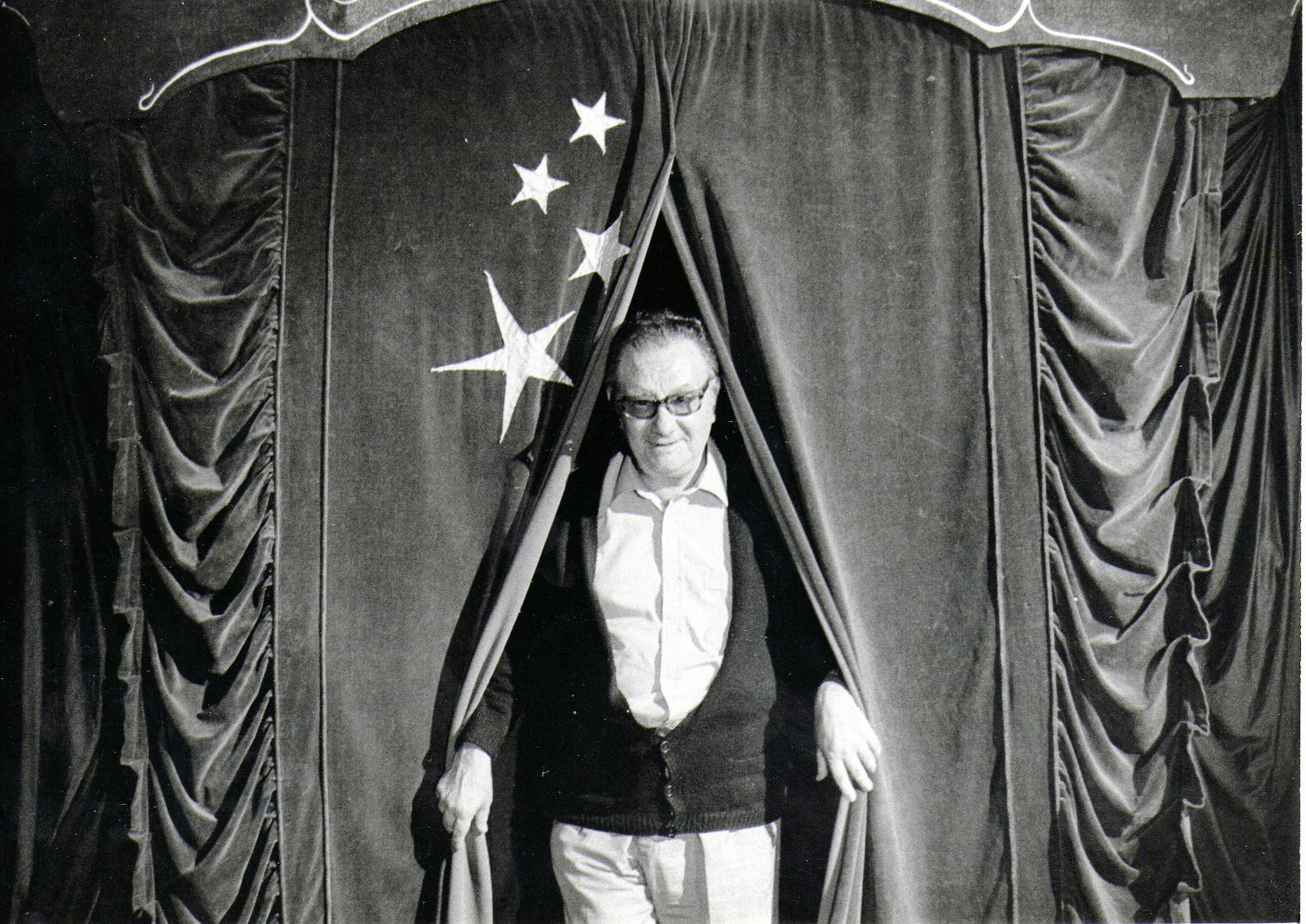

The Institute for Catalan Studies (IEC), Joan Brossa Foundation and Escenari Joan Brossa were the core venues for the 2nd International Symposium Joan Brossa: Trees vary depending on the terrain, held 7 and 8 November. The symposium aimed to “promote new readings” of the author, and featured poets, translators, scholars and critics like Perejaume, Enric Casasses, John London, Jordi Marrugat, Eduard Escoffet and Ronald Polito, and many more.

To share the experience of the translators who have made it possible for Brossa’s work to live on in other languages, Llull invited Victoria Pradilla and Alfonso Alegre (translators of Suite tràmpol and El compte enrere), and Marc Audí (translator of Sumari astral and an anthology published by Editions de l’Amandier), who have brought the poet’s verses to Spanish and French, respectively. Other participants in the conversation at Ateneu Barcelonès, with collaboration from the Joan Brossa Foundation and PEN Català, included Manuel Guerrero (curator of Joan Brossa Year) and Glòria Bordons (professor, researcher and expert in Brossa).

At the event, participants shared their interests, the way they approach a text, favourites and ideas of what makes this work so extraordinary and hard to translate. “The poet’s complexity has led him to be misread, even trivialised,” noted Bordons. “He could write sestinas, but he also showed enormous complexity in short poems. And we’ve found that a lot of the work out there isn’t properly translated. Because Brossa’s work is constructed in a way that is typical of Catalan and many translators haven’t grasped it.”

Manuel Guerrero highlights the fact that the poet worked “in all registers of the language, including oral Catalan, the spoken language.” His uniqueness, which was always overseen and guided by Andreu Rossinyol, means that some translations, like those into Spanish, a very close language, are totally biased. “They’re false friends,” adds Alegre. “It also happens with other translations from Catalan into Spanish, by people who think they have a good mastery of Spanish but just do a direct copy in too many cases. The way you have to write in Spanish is different from how it sounds in Catalan. It’s not as easy as it seems.”

Translators have to be creative, too

“You have to master the target language to do any translation,” explains Alegre. Communicating vessels that mean translators have to be creative, too. “When translating a sonnet or a sestina, you normally keep the iambic pentameter but not the rhyme, because that would be the easiest way to betray the original. But Brossa forces you, because he plays with the rhymes and, if you don’t do the same, the poem is dead.” So, “It is hard to combine the poet’s creativity and his literal meaning.”

“Translating Brossa, Alfonso and I worked as a team, sharing the work,” explains Pradilla, “I did a first pass and then, as he knows more about the formal aspects, he polished it. We would play like this, sometimes for days at a time,” in what turned out to be a nearly perfect collaboration, which Brossa himself called the best to express his poems in Spanish. For Guerrero, it’s clear: “With Brossa, the translator has to be a poet, too. Otherwise, it’s impossible to do it well.”

French translator Marc Audí remembers his first encounter with Brossa, as a reader: “It was through his visual poetry, which I was very drawn to as a kid.” Later on, he came to discover the written poems. “I remember buying Romancets del dragolí in 2011. I was living in France and Catalan was secondary. I thought that title, straight out of Cavall fort, clearly explained what the book was all about. But I was absolutely fascinated.”

“Highly popular, erudite, wise” language

Audí was inundated with the culture “of this highly popular, erudite, wise language of Brossa. In his work, the words don’t flow easily. Quite the contrary. In Em va fer Joan Brossa, none of the language is commonplace. It’s all artisanal language, but at the same time extremely tangled.” After his first reading, Audí discovered Sumari astral, which he would later translate into French. “For me, it is the culmination of his poetry.”

“When translating Brossa, you can be tempted to not stray far from the Catalan. And that gives you a French rendering that is completely uninteresting, as I’ve seen. You have to give the language a bit more weight.” Like with Catalan: Brossa’s language isn’t the same today. “And it can’t be in French either. It has to be like the language 30 or 40 years ago, and this is where I needed help from friends.”

“Brossa’s language is full of those absolute truths: permanent riddles,” he explains. But it isn’t fanciful language, either. It’s very controlled.” When you translate, you have to be able to recreate that tone without it seeming ridiculous. “Brossa’s language isn’t confetti and streamers. It’s very descriptive, very rooted in what is happening. You have to recreate it in French without it seeming like instructions for a washing machine or something frivolous. Personally, it’s been good for me to have genuine French friends of a certain age, who have been able to help me recreate the French spoken in the 1960s. It’s the accent, the language itself, the vocabulary and the grammar.” Audí, in fact, admits he has felt “a bit young” for some of Brossa’s things, like the Striptís.

Life: magic and performance

“I discovered Joan Brossa at university,” remembers Alegre. “My personal contact with him came later, in several interviews.” “No one introduced him to us,” adds Pradilla. “We just popped by his house, and visited him in his famous workshop, and told him about what we were doing, without any go-between. I was surprised that he always kept his keys in the lock.”

“To speak about Brossa, you have to speak about a lot of things, experiences, loads of stories,” Alegre breaks in again. “For him, life was a performance, magic and fun. He always gave you a lot to work with. I remember one Ash Wednesday, at a panel discussion with us, Català-Roca, Hausson the magician and his wife, dressed up as Little Red Riding Hood with her basket.”

“There was also a geisha and a nun, but not in fancy dress, real ones,” adds Pradilla. “Brossa seemed to conjure magic and poetry out of reality. I remember, next to our panel discussion, there was a booth with two security guards, because there was a minister inside. He was fascinating. He provoked one-of-a-kind, unpredictable situations.”

Brossa, extraordinarily current

Brossa is a complex, multifaceted creator: designer, poster-maker, artist, playwright, poet. Is his work appreciated today? “Not in France, no,” Audí says. “Those who know about experimental poetry know of him. But who has heard of Verdaguer or Maragall in France? No one. Really, we can’t blame them. Some translations don’t get wide circulation. That’s just how it is. And the people who do know Brossa in France know him for his visual work.”

“In Spain and Latin America, Brossa has got more publicity,” explains Guerrero. “But it’s also true that he is better known as a visual artist than for his written poetry. The breadth of his work isn’t well known. A lot of his work has also been translated into Portuguese, by Roland Polito who has done a great job,” notes Bordons.

In any case, everyone agrees that his work is still very fresh and current today. “There are things that are still very relevant because he knows how to make you feel intelligent,” Audí explains. “Brossa has the ability to control his poems and open them up to his readers. His poetry questions you. But we also have to note that some of his work seems very old-fashioned now. Like, for example, Les odes sàfiques, which are extraordinary, but not current. But it doesn’t all have to be. That’s no problem!”

In terms of legacy, Brossa is alive and well. “No one has ever explained Brossa to me as well as Perejaume did in his conference at the 2nd Symposium. And, also, Casasses, who brought out the character he had created, so unpleasant,” says Audí. “The best at explaining Brossa have been two poets. Will that continue? Of course. The new generation, full of intertextuality (Maria Sevilla, Maria Cabrera, Raquel Santanera, Pol Guasch) all do collections with five epigraphs, quotes inside, thanks, excerpts, etc. You see Brossa less in these young people, it’s true. But if you go see them at Horiginal, they’ll all say he influenced them. They all speak of him as one of the classics.”

“Brossa’s dialogue transcended poetry,” says Alegre. “Musicians, artists, designers. That made him very different. This dialogue with the arts also made him very important, and powerful. And also, Brossa hated pedantry.” In the end, aspects that explain the exceptionalness of this author who was close and intense, popular and complex, powerful and precise, with one foot in the future and the other rooted in tradition, as Victoria Pradilla, Alfonso Alegre, Marc Audí, Manuel Guerrero and Glòria Bordons proved in this conversation that further demonstrates how relevant Joan Brossa still is. Unique, unpredictable, irreplaceable.